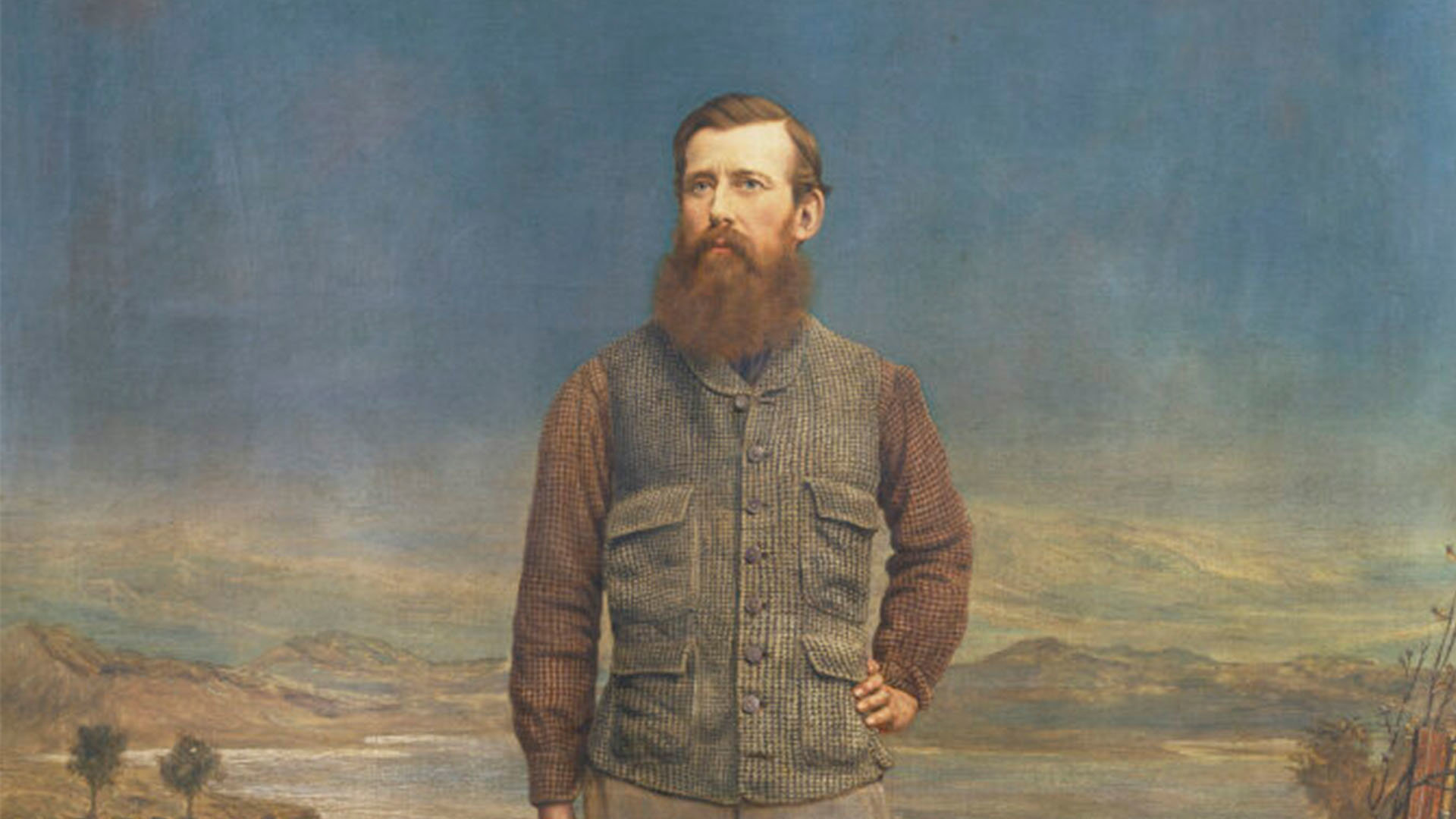

This portrait shows John Hanning Speke (1827-1864) in front of a view of Lake Victoria (Nyanza), the lake Speke had renamed as part of the European search for the source of the White Nile River.

Speke is surrounded by the instruments of exploration: a sextant, pocket watch and rifle. Interestingly, he is shown alone, despite having had the aid of hundreds of Africans during his expeditions. This trope of a heroic and solitary European explorer came to prominence in the Victorian era and was strongly associated with the work of the Royal Geographical Society.

The Society, which, since its founding in 1830, had become the main arbiter of British exploration thanks to its close ties to government and empire, set its sights on finding the source of the White Nile in the 1850s. James Bruce, whose portrait is also on the wall in the Map Room, had followed the smaller Blue Nile to its source in 1770, following in the earlier footsteps of the Jesuit Pedro Paez in 1618.

European geographers had long been fascinated by the possible fount of one of the world’s most important rivers. Mapmakers had abandoned the Ptolemaic hypothesis of twin lakes in the Mountains of the Moon, but Europeans were still in the dark as to the actual wellspring of the waterway. Additionally, the British and Indian governments were eager to learn more about the political and geographical organisation of the interior of Eastern Africa, information that would eventually aid European powers as they divided Africa into imperial spheres of control as part of the Scramble for Africa in the late-nineteenth century.

Speke, an army officer and avid trophy hunter, joined a Society expedition to East Africa led by Richard Burton. They set off in June 1857 and made it to Lake Tanganyika by February 1858.

Their movement depended not only on guides, but on hundreds of African scouts, hunters, porters, negotiators, and interpreters, as well as on local leaders who granted permission to access territory and waterways.

Such dependence is typical of imperial exploration in this period. While Western travellers tended to be credited with ‘discoveries’, their knowledge, supplies, and very survival often rested on the contributions of local peoples.

After departing Lake Tanganyika, Speke left an ill Burton at Tabora and pressed on to another body of water, Lake Nyanza (one of several local names). He renamed it for Queen Victoria and surmised that he had found the source of the great river. Burton thought this hypothesis likely but knew more definitive evidence would be needed.

The Society agreed, quickly tasking Speke and J. A. Grant with a return expedition in 1860. They were led by East African guides, including Sidi Mubarak Bombay. It took months of negotiation with Mutesa, leader of Buganda, for Speke to gain access to the spot where the Nile issues from Lake Victoria. While waiting, Speke interacted with a variety of local groups, leading him to develop a racist theory of ethnic lineage, the Hamitic hypothesis, which later fuelled discord and violence. Grant, whose leg was ulcerated, was not present when Speke finally visited what he called Ripon Falls, leaving Speke open to criticism upon his return to London in 1863.

At first, Speke was celebrated as a heroic explorer. The Society arranged a special meeting to laud his work where eager attendees broke windows to gain entry. To bolster his credibility, Speke brought several of his informants and aids on stage with him, including an African boy, George Francis Tembo. Many were still sceptical, however, including Burton. The explorers’ disagreements grew heated and, in September 1864, the Society, eager to avoid further controversy, coordinated the meeting of the geographical section of the British Association to serve as a debate between the men. The day before, however, Speke died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound while out hunting.

Further reading

Bridges, Roy, editor. A Walk Across Africa: J. A. Grant’s Account of the Nile Expedition of 1860-1863. London: The Hakluyt Society, 2018.

Bridges, Roy. "Speke, John Hanning (1827–1864), explorer in Africa." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Hidden Histories of Exploration, online exhibition by Felix Driver and Lowri Jones with the Royal Geographical Society.

Millard, Candace. River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile. London: Swift Press, 2022.

Robinson, Michael F. The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.