John Barrow (1764-1848) was born in Ulverston in Cumbria in 1764 and at the age of just 14 he started work as a superintending clerk at an iron foundry in Liverpool. Two years later he joined a whaling expedition to Greenland which began his lifelong interest in nautical matters.

On his return from Greenland, he taught mathematics in a private school in Greenwich where he made the acquaintance of Sir George Staunton whose son he was teaching. In 1792 he accompanied Staunton on Lord Macartney’s embassy to China. This diplomatic mission did not achieve its aims, but Barrow developed a keen interest in Chinese affairs.

Between 1800 and 1804 he lived in South Africa where he travelled and wrote extensively. He would have stayed had not Cape Colony been briefly returned to the Netherlands.

On his return to London, he was appointed Second Secretary (Permanent Secretary) to the Admiralty, an influential position he held for the next 40 years. Following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain had a large number of ships and officers left redundant, so to keep them occupied Barrow devised an ambitious programme of exploration, most notably to West Africa and the Arctic.

In search of a Northwest Passage

The Royal Naval expeditions to try and find a Northwest Passage – a sea route between Northern Europe and the Far East – began in 1818 with the voyage of Captain John Ross in the ships Isabella and Alexander.

This expedition had very limited success and there followed three expeditions led by Captain William Edward Parry that were more successful but still failed to find a viable route to the Far East.

The final expedition in search of a Northwest Passage under Barrow’s direction was that of Sir John Franklin, husband of Lady Jane Franklin. There were high hopes for this well-equipped expedition, led by experienced captains, but it was to end in total disaster with the deaths of every crew member of the ships Erebus and Terror, over 120 men. Over the following decade more ships and men were lost trying to discover the fate of Franklin and his crew.

Critique on Barrow's pursuits

In Barrow’s time there were critics of his single-minded pursuit of a Northwest Passage and after his death, once the fate of Franklin had been discovered, the Royal Navy sent no more expeditions in search of a Northwest Passage. Fergus Fleming, the author of a history of Barrow’s expeditions, wrote that, "perhaps no other man in the history of exploration has expended so much money and so many lives in so desperately pointless a dream. "

Barrow and the Society

After retiring in 1845 Barrow devoted the rest of his life to writing a history of the Arctic voyages from 1818 onwards as well as an autobiography. Outside of the Admiralty, he was one of the founding Fellows of the Society.

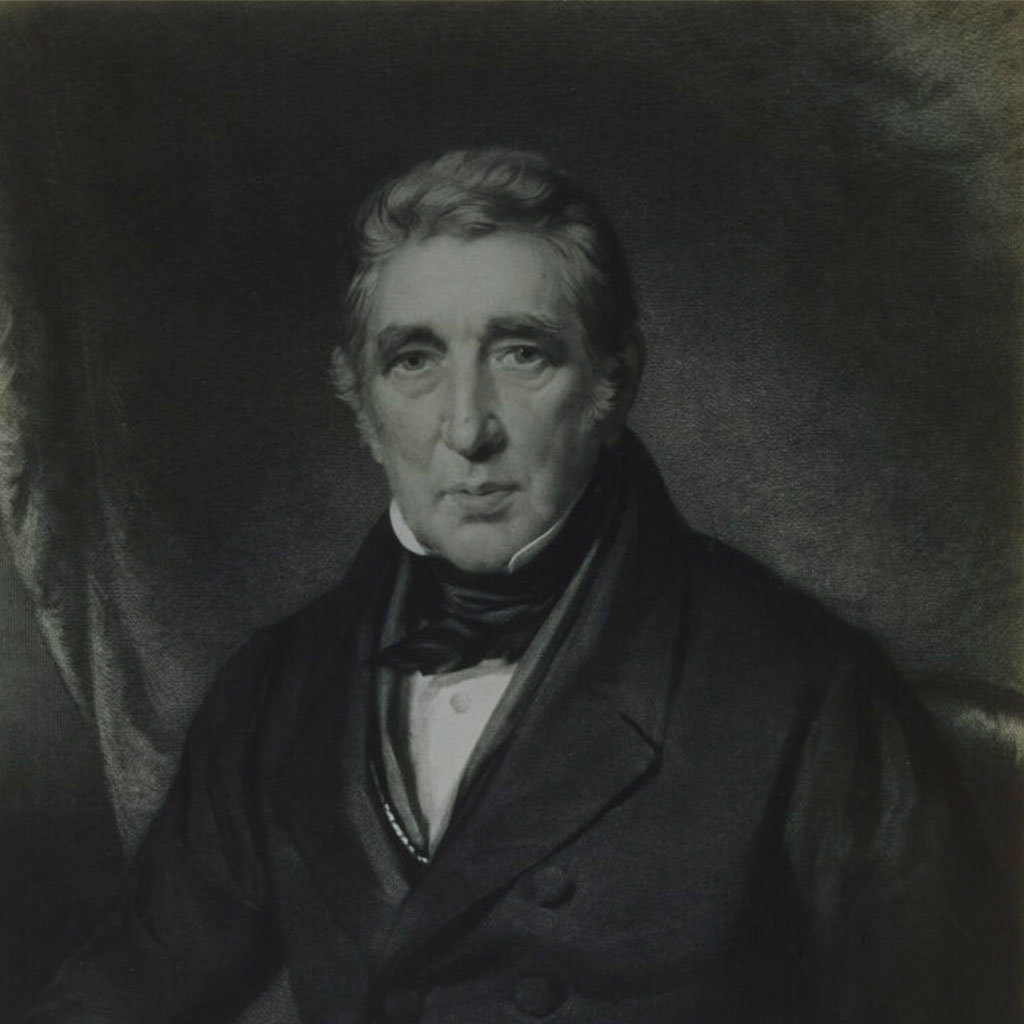

The oil on canvas portrait of Barrow in our Collection is after a portrait by John Jackson in the John Murray Collection.

Further reading

An autobiographical memoir of Sir John Barrow, including reflections, observations, and reminiscences at home and abroad, fr. early life to advanced age. London: John Murray, 1847.

Cameron, J. M. R. "Barrow, Sir John, first baronet (1764–1848), promoter of exploration and author." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Cameron, J. R. “John Barrow, the Quarterly's Imperial Reviewer.” In Conservatism and the Quarterly Review: A Critical Analysis, edited by Jonathan Cutmore, n.p (17 pages, ebook). London: Routledge, 2008.

Driver, Felix. Geography militant: cultures of exploration and empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001. See especially chapter 2.

Fleming, Fergus. Barrow's boys. London: Granta Books, 1998.

Ritchie, G. S. “Sir John Barrow, Bart., F. R. S.” The Geographical Journal 130, no. 3 (1964): 350-4.