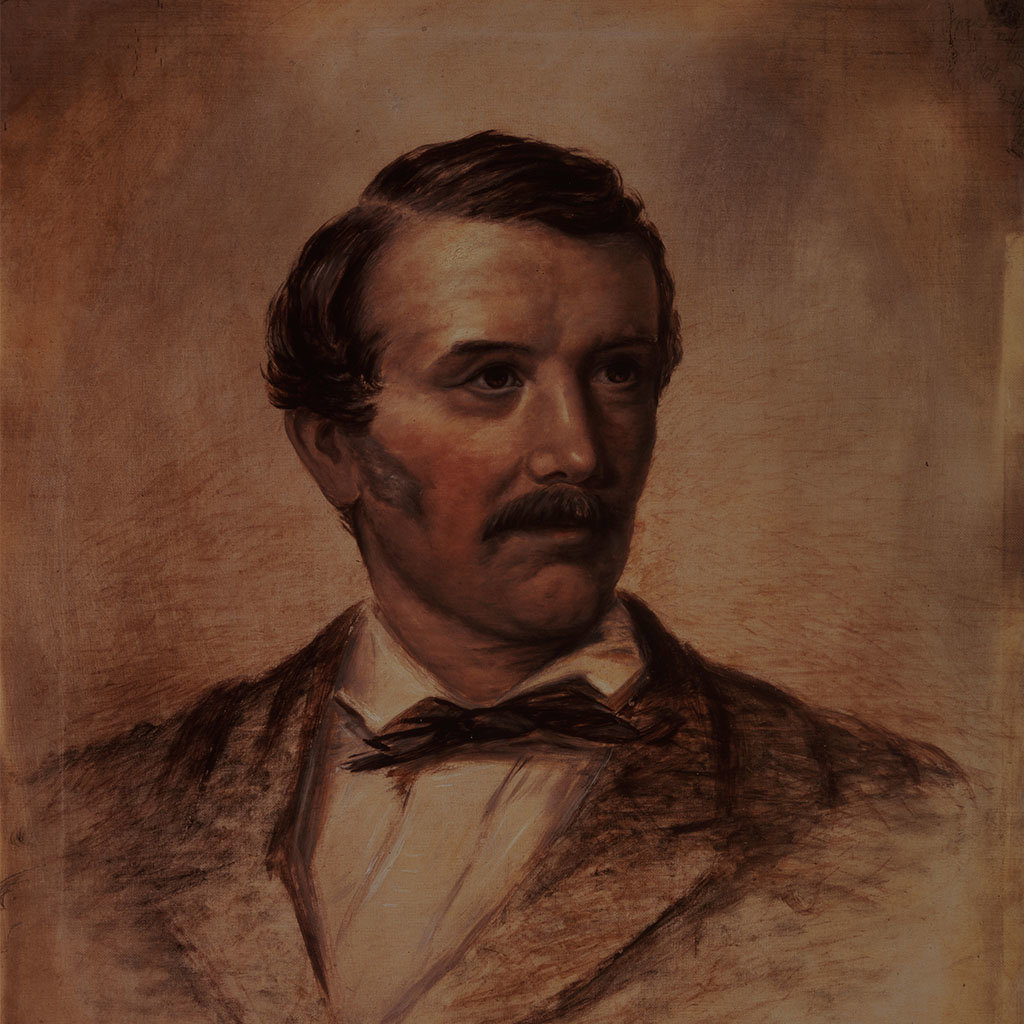

David Livingstone was a doctor, missionary, and explorer who had close ties to the Society. Today, the Society holds many artefacts and papers related to his travels. These objects, including this portrait, inspire questions about exploration’s ties to religion and empire, as well as about the role of local intermediaries who often aided European travellers.

Young Livingstone worked in the mills of Glasgow. Raised by a devout family that valued education, he sought to learn medicine as part of a Christian mission. To this end, he passed his medical exams and was ordained in 1840.

While studying, Livingstone had heard London Missionary Society lectures and met their missionaries working in southern Africa, sparking an interest in the region.

Start of missionary travels and renaming Victoria Falls

Livingstone began his missionary among the Tswana peoples, always with an eye to pushing farther inland and away from established missions. Livingstone heard of a lake in the interior and journeyed to what turned out to be Lake Ngami. This resulted in a £25 prize from the Society.

Next, he set his sights on the Zambezi River and crossing Africa. As part of this venture, he became one of the first Europeans to see Mosi-oa-Tunya, ‘the waters that thunder’—he renamed the waterfall Victoria Falls.

Livingstone set out again in 1866, this time to seek the headwaters of the Nile, which he thought were related to Lakes Nyasa and Tanganyika, and later the Lualaba River. It was on this quest that Henry Morton Stanley eventually met with Livingstone, in Ujiji, in November 1871.

Livingstone continued his quest, dying in 1873. His body reached London a year later, where it was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Livingstone's legacy

Livingstone was revered after his death, becoming a symbol of benevolent empire—a missionary who abhorred the slave trade and thought that missionisation should go hand-in-hand with commerce.

Today, researchers try to look beyond the saintly view of Livingstone that prevailed after his death and instead are interested in other topics, especially the many local people who helped Livingstone survive his travels, the organisation of his expeditions, the significance of his writings, and the nature of Victorian celebrity culture. Many of these scholars come to the Society to access our extensive Livingstone collections.

In addition to the portrait, our Collection holds part of the tree bark and a photo of the Mpundu tree under which Livingstone's heart was buried.

Further reading

Dritsas, Lawrence. Zambesi: David Livingstone and Expeditionary Science in Africa. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Driver, Felix. Geography militant: cultures of exploration and empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

Roberts, A. D. "Livingstone, David (1813–1873), explorer and missionary." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Ross, Andrew C. David Livingstone: mission and empire. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2006.