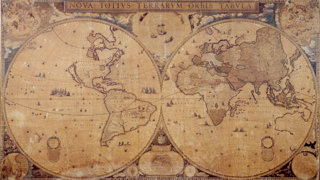

This map is one of only two known examples of this impressive second edition (c.1655-58) of Joan Blaeu’s (1596-1673) double-hemisphere world map.

The equatorial stereographic projection preserves cartographic conventions of the time, such as California as an island, and speaks to the political situation of Europe when it was created – the first edition was made to commemorate the Peace of Westphalia (1648). It also provides insight into the competitive world of mapmaking in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.

While the Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War, which had ravaged much of Europe, this map was part of an ongoing competition between the mapmaking firms of Blaeu and Hondius.

Both firms were set up in Amsterdam in the early years of the seventeenth century and both continued with subsequent generations of family members.When one published an atlas, globe, or wall map, the other would answer with a similar or slightly grander item. Their skill and output helped to make Amsterdam the centre of cartographic production in Europe for 75 years.

Blaeu's double-hemisphere map

This map is certainly a luxurious item intended for an elite audience who would contemplate its details on the walls of wealthy homes or offices.

Blaeu chose not to include a southern continent, as its existence was not confirmed, but he did record the Dutch East India Company’s run-ins with the northern and western coasts of Australia – Blaeu was the hydrographer of the Company and therefore had access to privileged information.

Insets in the corners show the poles and celestial maps of the northern and southern hemispheres, while in the centre are the solar system hypotheses of Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, and Copernicus.

Blaeu's map and its significance for the Society

The map came to the Society as a gift from Sir Arthur Paget in 1920. Paget’s career was an imperial one; he served in the First Asante Expedition, which resulted in the destruction of Kumasi and the defeat of the Asante Empire. He later served in Sudan, Myanmar, South Africa, and Ireland. The Society and our Collections have benefited from the travels and connections of our Fellows since we were founded, making conversations concerning provenance and the mobility of objects across borders important to the Society.

This map also brings up issues of document survival. We can only learn of the past through what survives. This is one of only two known examples of this map; the other example has 20 sheets of text at the bottom and is held at the Maritime Museum in Rotterdam. Why this example does not have the text, and whether it ever did, is not known.

Open, comparative discussions with other repositories and individuals help us to learn about our Collections and the librarians at the Society eagerly engage in such discussions regularly.

Further reading

Koeman, Cornelis, Günter Schilder, Marco van Egmond, and Peter van der Krogt. ‘Commercial Cartography and Map Production in the Low Countries, 1500–ca. 1672.’ In History of Cartography Volume Three (Part 2): Cartography in European Renaissance, edited by David Woodward, 1296-1383. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Zandvliet, Kees. Mapping for Money: Maps, Plans, and Topographic Paintings and Their Role in Dutch Overseas Expansion During the 16th and 17th Centuries. Amsterdam: Batavian Lion International, 1998.